423 lines

16 KiB

Markdown

423 lines

16 KiB

Markdown

# Contributing Quick Start

|

|

|

|

Rust Analyzer is an ordinary Rust project, which is organized as a Cargo

|

|

workspace, builds on stable and doesn't depend on C libraries. So, just

|

|

|

|

```

|

|

$ cargo test

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

should be enough to get you started!

|

|

|

|

To learn more about how rust-analyzer works, see

|

|

[./architecture.md](./architecture.md) document.

|

|

|

|

We also publish rustdoc docs to pages:

|

|

|

|

https://rust-analyzer.github.io/rust-analyzer/ra_ide/

|

|

|

|

Various organizational and process issues are discussed in this document.

|

|

|

|

# Getting in Touch

|

|

|

|

Rust Analyzer is a part of [RLS-2.0 working

|

|

group](https://github.com/rust-lang/compiler-team/tree/6a769c13656c0a6959ebc09e7b1f7c09b86fb9c0/working-groups/rls-2.0).

|

|

Discussion happens in this Zulip stream:

|

|

|

|

https://rust-lang.zulipchat.com/#narrow/stream/185405-t-compiler.2Fwg-rls-2.2E0

|

|

|

|

# Issue Labels

|

|

|

|

* [good-first-issue](https://github.com/rust-analyzer/rust-analyzer/labels/good%20first%20issue)

|

|

are good issues to get into the project.

|

|

* [E-has-instructions](https://github.com/rust-analyzer/rust-analyzer/issues?q=is%3Aopen+is%3Aissue+label%3AE-has-instructions)

|

|

issues have links to the code in question and tests.

|

|

* [E-easy](https://github.com/rust-analyzer/rust-analyzer/issues?q=is%3Aopen+is%3Aissue+label%3AE-easy),

|

|

[E-medium](https://github.com/rust-analyzer/rust-analyzer/issues?q=is%3Aopen+is%3Aissue+label%3AE-medium),

|

|

[E-hard](https://github.com/rust-analyzer/rust-analyzer/issues?q=is%3Aopen+is%3Aissue+label%3AE-hard),

|

|

labels are *estimates* for how hard would be to write a fix.

|

|

* [fun](https://github.com/rust-analyzer/rust-analyzer/issues?q=is%3Aopen+is%3Aissue+label%3Afun)

|

|

is for cool, but probably hard stuff.

|

|

|

|

# CI

|

|

|

|

We use GitHub Actions for CI. Most of the things, including formatting, are checked by

|

|

`cargo test` so, if `cargo test` passes locally, that's a good sign that CI will

|

|

be green as well. The only exception is that some long-running tests are skipped locally by default.

|

|

Use `env RUN_SLOW_TESTS=1 cargo test` to run the full suite.

|

|

|

|

We use bors-ng to enforce the [not rocket science](https://graydon2.dreamwidth.org/1597.html) rule.

|

|

|

|

You can run `cargo xtask install-pre-commit-hook` to install git-hook to run rustfmt on commit.

|

|

|

|

# Code organization

|

|

|

|

All Rust code lives in the `crates` top-level directory, and is organized as a

|

|

single Cargo workspace. The `editors` top-level directory contains code for

|

|

integrating with editors. Currently, it contains the plugin for VS Code (in

|

|

TypeScript). The `docs` top-level directory contains both developer and user

|

|

documentation.

|

|

|

|

We have some automation infra in Rust in the `xtask` package. It contains

|

|

stuff like formatting checking, code generation and powers `cargo xtask install`.

|

|

The latter syntax is achieved with the help of cargo aliases (see `.cargo`

|

|

directory).

|

|

|

|

# Launching rust-analyzer

|

|

|

|

Debugging the language server can be tricky: LSP is rather chatty, so driving it

|

|

from the command line is not really feasible, driving it via VS Code requires

|

|

interacting with two processes.

|

|

|

|

For this reason, the best way to see how rust-analyzer works is to find a

|

|

relevant test and execute it (VS Code includes an action for running a single

|

|

test).

|

|

|

|

However, launching a VS Code instance with a locally built language server is

|

|

possible. There's **"Run Extension (Debug Build)"** launch configuration for this.

|

|

|

|

In general, I use one of the following workflows for fixing bugs and

|

|

implementing features.

|

|

|

|

If the problem concerns only internal parts of rust-analyzer (i.e. I don't need

|

|

to touch the `rust-analyzer` crate or TypeScript code), there is a unit-test for it.

|

|

So, I use **Rust Analyzer: Run** action in VS Code to run this single test, and

|

|

then just do printf-driven development/debugging. As a sanity check after I'm

|

|

done, I use `cargo xtask install --server` and **Reload Window** action in VS

|

|

Code to sanity check that the thing works as I expect.

|

|

|

|

If the problem concerns only the VS Code extension, I use **Run Installed Extension**

|

|

launch configuration from `launch.json`. Notably, this uses the usual

|

|

`rust-analyzer` binary from `PATH`. For this, it is important to have the following

|

|

in your `settings.json` file:

|

|

```json

|

|

{

|

|

"rust-analyzer.serverPath": "rust-analyzer"

|

|

}

|

|

```

|

|

After I am done with the fix, I use `cargo

|

|

xtask install --client-code` to try the new extension for real.

|

|

|

|

If I need to fix something in the `rust-analyzer` crate, I feel sad because it's

|

|

on the boundary between the two processes, and working there is slow. I usually

|

|

just `cargo xtask install --server` and poke changes from my live environment.

|

|

Note that this uses `--release`, which is usually faster overall, because

|

|

loading stdlib into debug version of rust-analyzer takes a lot of time. To speed

|

|

things up, sometimes I open a temporary hello-world project which has

|

|

`"rust-analyzer.withSysroot": false` in `.code/settings.json`. This flag causes

|

|

rust-analyzer to skip loading the sysroot, which greatly reduces the amount of

|

|

things rust-analyzer needs to do, and makes printf's more useful. Note that you

|

|

should only use the `eprint!` family of macros for debugging: stdout is used for LSP

|

|

communication, and `print!` would break it.

|

|

|

|

If I need to fix something simultaneously in the server and in the client, I

|

|

feel even more sad. I don't have a specific workflow for this case.

|

|

|

|

Additionally, I use `cargo run --release -p rust-analyzer -- analysis-stats

|

|

path/to/some/rust/crate` to run a batch analysis. This is primarily useful for

|

|

performance optimizations, or for bug minimization.

|

|

|

|

# Code Style & Review Process

|

|

|

|

Our approach to "clean code" is two-fold:

|

|

|

|

* We generally don't block PRs on style changes.

|

|

* At the same time, all code in rust-analyzer is constantly refactored.

|

|

|

|

It is explicitly OK for a reviewer to flag only some nits in the PR, and then send a follow-up cleanup PR for things which are easier to explain by example, cc-ing the original author.

|

|

Sending small cleanup PRs (like renaming a single local variable) is encouraged.

|

|

|

|

## Scale of Changes

|

|

|

|

Everyone knows that it's better to send small & focused pull requests.

|

|

The problem is, sometimes you *have* to, eg, rewrite the whole compiler, and that just doesn't fit into a set of isolated PRs.

|

|

|

|

The main things to keep an eye on are the boundaries between various components.

|

|

There are three kinds of changes:

|

|

|

|

1. Internals of a single component are changed.

|

|

Specifically, you don't change any `pub` items.

|

|

A good example here would be an addition of a new assist.

|

|

|

|

2. API of a component is expanded.

|

|

Specifically, you add a new `pub` function which wasn't there before.

|

|

A good example here would be expansion of assist API, for example, to implement lazy assists or assists groups.

|

|

|

|

3. A new dependency between components is introduced.

|

|

Specifically, you add a `pub use` reexport from another crate or you add a new line to the `[dependencies]` section of `Cargo.toml`.

|

|

A good example here would be adding reference search capability to the assists crates.

|

|

|

|

For the first group, the change is generally merged as long as:

|

|

|

|

* it works for the happy case,

|

|

* it has tests,

|

|

* it doesn't panic for the unhappy case.

|

|

|

|

For the second group, the change would be subjected to quite a bit of scrutiny and iteration.

|

|

The new API needs to be right (or at least easy to change later).

|

|

The actual implementation doesn't matter that much.

|

|

It's very important to minimize the amount of changed lines of code for changes of the second kind.

|

|

Often, you start doing a change of the first kind, only to realise that you need to elevate to a change of the second kind.

|

|

In this case, we'll probably ask you to split API changes into a separate PR.

|

|

|

|

Changes of the third group should be pretty rare, so we don't specify any specific process for them.

|

|

That said, adding an innocent-looking `pub use` is a very simple way to break encapsulation, keep an eye on it!

|

|

|

|

Note: if you enjoyed this abstract hand-waving about boundaries, you might appreciate

|

|

https://www.tedinski.com/2018/02/06/system-boundaries.html

|

|

|

|

## Order of Imports

|

|

|

|

We separate import groups with blank lines

|

|

|

|

```rust

|

|

mod x;

|

|

mod y;

|

|

|

|

use std::{ ... }

|

|

|

|

use crate_foo::{ ... }

|

|

use crate_bar::{ ... }

|

|

|

|

use crate::{}

|

|

|

|

use super::{} // but prefer `use crate::`

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

## Import Style

|

|

|

|

Items from `hir` and `ast` should be used qualified:

|

|

|

|

```rust

|

|

// Good

|

|

use ra_syntax::ast;

|

|

|

|

fn frobnicate(func: hir::Function, strukt: ast::StructDef) {}

|

|

|

|

// Not as good

|

|

use hir::Function;

|

|

use ra_syntax::ast::StructDef;

|

|

|

|

fn frobnicate(func: Function, strukt: StructDef) {}

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

Avoid local `use MyEnum::*` imports.

|

|

|

|

Prefer `use crate::foo::bar` to `use super::bar`.

|

|

|

|

## Order of Items

|

|

|

|

Optimize for the reader who sees the file for the first time, and wants to get the general idea about what's going on.

|

|

People read things from top to bottom, so place most important things first.

|

|

|

|

Specifically, if all items except one are private, always put the non-private item on top.

|

|

|

|

Put `struct`s and `enum`s first, functions and impls last.

|

|

|

|

Do

|

|

|

|

```rust

|

|

// Good

|

|

struct Foo {

|

|

bars: Vec<Bar>

|

|

}

|

|

|

|

struct Bar;

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

rather than

|

|

|

|

```rust

|

|

// Not as good

|

|

struct Bar;

|

|

|

|

struct Foo {

|

|

bars: Vec<Bar>

|

|

}

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

## Variable Naming

|

|

|

|

We generally use boring and long names for local variables ([yay code completion](https://github.com/rust-analyzer/rust-analyzer/pull/4162#discussion_r417130973)).

|

|

The default name is a lowercased name of the type: `global_state: GlobalState`.

|

|

Avoid ad-hoc acronyms and contractions, but use the ones that exist consistently (`db`, `ctx`, `acc`).

|

|

The default name for "result of the function" local variable is `res`.

|

|

|

|

## Preconditions

|

|

|

|

Function preconditions should generally be expressed in types and provided by the caller (rather than checked by callee):

|

|

|

|

```rust

|

|

// Good

|

|

fn frbonicate(walrus: Walrus) {

|

|

...

|

|

}

|

|

|

|

// Not as good

|

|

fn frobnicate(walrus: Option<Walrus>) {

|

|

let walrus = match walrus {

|

|

Some(it) => it,

|

|

None => return,

|

|

};

|

|

...

|

|

}

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

## Premature Pessimization

|

|

|

|

While we don't specifically optimize code yet, avoid writing code which is slower than it needs to be.

|

|

Don't allocate a `Vec` where an iterator would do, don't allocate strings needlessly.

|

|

|

|

```rust

|

|

// Good

|

|

use itertools::Itertools;

|

|

|

|

let (first_word, second_word) = match text.split_ascii_whitespace().collect_tuple() {

|

|

Some(it) => it,

|

|

None => return,

|

|

}

|

|

|

|

// Not as good

|

|

let words = text.split_ascii_whitespace().collect::<Vec<_>>();

|

|

if words.len() != 2 {

|

|

return

|

|

}

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

## Documentation

|

|

|

|

For `.md` and `.adoc` files, prefer a sentence-per-line format, don't wrap lines.

|

|

If the line is too long, you want to split the sentence in two :-)

|

|

|

|

## Commit Style

|

|

|

|

We don't have specific rules around git history hygiene.

|

|

Maintaining clean git history is encouraged, but not enforced.

|

|

We use rebase workflow, it's OK to rewrite history during PR review process.

|

|

|

|

Avoid @mentioning people in commit messages, as such messages create a lot of duplicate notification traffic during rebases.

|

|

|

|

# Architecture Invariants

|

|

|

|

This section tries to document high-level design constraints, which are not

|

|

always obvious from the low-level code.

|

|

|

|

## Incomplete syntax trees

|

|

|

|

Syntax trees are by design incomplete and do not enforce well-formedness.

|

|

If an AST method returns an `Option`, it *can* be `None` at runtime, even if this is forbidden by the grammar.

|

|

|

|

## LSP independence

|

|

|

|

rust-analyzer is independent from LSP.

|

|

It provides features for a hypothetical perfect Rust-specific IDE client.

|

|

Internal representations are lowered to LSP in the `rust-analyzer` crate (the only crate which is allowed to use LSP types).

|

|

|

|

## IDE/Compiler split

|

|

|

|

There's a semi-hard split between "compiler" and "IDE", at the `ra_hir` crate.

|

|

Compiler derives new facts about source code.

|

|

It explicitly acknowledges that not all info is available (i.e. you can't look at types during name resolution).

|

|

|

|

IDE assumes that all information is available at all times.

|

|

|

|

IDE should use only types from `ra_hir`, and should not depend on the underling compiler types.

|

|

`ra_hir` is a facade.

|

|

|

|

## IDE API

|

|

|

|

The main IDE crate (`ra_ide`) uses "Plain Old Data" for the API.

|

|

Rather than talking in definitions and references, it talks in Strings and textual offsets.

|

|

In general, API is centered around UI concerns -- the result of the call is what the user sees in the editor, and not what the compiler sees underneath.

|

|

The results are 100% Rust specific though.

|

|

|

|

## Parser Tests

|

|

|

|

Tests for the parser (`ra_parser`) live in the `ra_syntax` crate (see `test_data` directory).

|

|

There are two kinds of tests:

|

|

|

|

* Manually written test cases in `parser/ok` and `parser/err`

|

|

* "Inline" tests in `parser/inline` (these are generated) from comments in `ra_parser` crate.

|

|

|

|

The purpose of inline tests is not to achieve full coverage by test cases, but to explain to the reader of the code what each particular `if` and `match` is responsible for.

|

|

If you are tempted to add a large inline test, it might be a good idea to leave only the simplest example in place, and move the test to a manual `parser/ok` test.

|

|

|

|

To update test data, run with `UPDATE_EXPECTATIONS` variable:

|

|

|

|

```bash

|

|

env UPDATE_EXPECTATIONS=1 cargo qt

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

# Logging

|

|

|

|

Logging is done by both rust-analyzer and VS Code, so it might be tricky to

|

|

figure out where logs go.

|

|

|

|

Inside rust-analyzer, we use the standard `log` crate for logging, and

|

|

`env_logger` for logging frontend. By default, log goes to stderr, but the

|

|

stderr itself is processed by VS Code.

|

|

|

|

To see stderr in the running VS Code instance, go to the "Output" tab of the

|

|

panel and select `rust-analyzer`. This shows `eprintln!` as well. Note that

|

|

`stdout` is used for the actual protocol, so `println!` will break things.

|

|

|

|

To log all communication between the server and the client, there are two choices:

|

|

|

|

* you can log on the server side, by running something like

|

|

```

|

|

env RA_LOG=gen_lsp_server=trace code .

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

* you can log on the client side, by enabling `"rust-analyzer.trace.server":

|

|

"verbose"` workspace setting. These logs are shown in a separate tab in the

|

|

output and could be used with LSP inspector. Kudos to

|

|

[@DJMcNab](https://github.com/DJMcNab) for setting this awesome infra up!

|

|

|

|

|

|

There are also two VS Code commands which might be of interest:

|

|

|

|

* `Rust Analyzer: Status` shows some memory-usage statistics. To take full

|

|

advantage of it, you need to compile rust-analyzer with jemalloc support:

|

|

```

|

|

$ cargo install --path crates/rust-analyzer --force --features jemalloc

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

There's an alias for this: `cargo xtask install --server --jemalloc`.

|

|

|

|

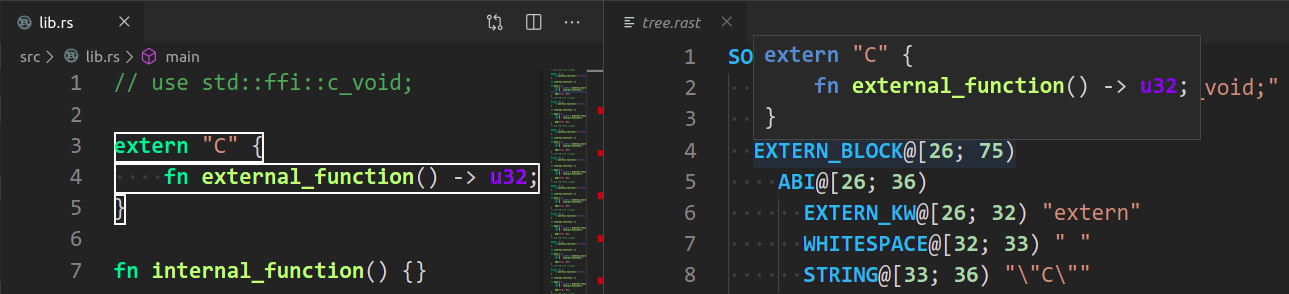

* `Rust Analyzer: Syntax Tree` shows syntax tree of the current file/selection.

|

|

|

|

You can hover over syntax nodes in the opened text file to see the appropriate

|

|

rust code that it refers to and the rust editor will also highlight the proper

|

|

text range.

|

|

|

|

If you trigger Go to Definition in the inspected Rust source file,

|

|

the syntax tree read-only editor should scroll to and select the

|

|

appropriate syntax node token.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

# Profiling

|

|

|

|

We have a built-in hierarchical profiler, you can enable it by using `RA_PROFILE` env-var:

|

|

|

|

```

|

|

RA_PROFILE=* // dump everything

|

|

RA_PROFILE=foo|bar|baz // enabled only selected entries

|

|

RA_PROFILE=*@3>10 // dump everything, up to depth 3, if it takes more than 10 ms

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

In particular, I have `export RA_PROFILE='*>10'` in my shell profile.

|

|

|

|

To measure time for from-scratch analysis, use something like this:

|

|

|

|

```

|

|

$ cargo run --release -p rust-analyzer -- analysis-stats ../chalk/

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

For measuring time of incremental analysis, use either of these:

|

|

|

|

```

|

|

$ cargo run --release -p rust-analyzer -- analysis-bench ../chalk/ --highlight ../chalk/chalk-engine/src/logic.rs

|

|

$ cargo run --release -p rust-analyzer -- analysis-bench ../chalk/ --complete ../chalk/chalk-engine/src/logic.rs:94:0

|

|

```

|